Brandon Julian

Personal website for projects, blog, and information.

Bayesian Statistics

by Brandon Julian

Starting Bayesian Statistics the Fun Way, by Will Kurt

So far this is an awesome book and I am looking forward to the rest, be sure to check it out.

In order to help myself understand some of the initial topics brought forward in literally the opening chapters of the book, I had to go out and research the formal definition of frequentist statistics.

What is Frequentist Stats?

The frequentist approach to stats is all about frequencies, distributions, and the law of large numbers. Taking the coin flip, if a fair coin is flipped an infinite number of times, one can expect to get an equal number of heads and tails. Or a probability of getting a heads (or tails) being .5 per flip based on this observed frequency. And therefore the fair coin flip has a binomial distribution of outcomes over infinite coin flips. The reason all of the infinities are important (law of large numbers) is that frequentist statistics only applies probabilities to repeated events observed over long periods of time.1 And it’s in this area that frequentism is apparently very different from Bayesian stats.

What is Bayesian Statistics?

So far, this is something I can comprehend on my own. However, since I have had a hard time figuring out how to explain the difference between Bayesian stats and frequentist stats without immediately quoting Will Kurt or another more experienced statistician. I can’t say I fully comprehend it. You don’t fully understand something until you can teach it right?

I’ll leave it up to Kurt here -

Bayesian statistics, on the other hand, is concerned with how probabilities represent how uncertain we are about a piece of information. In Bayesian terms, if the probability of getting heads in a coin toss is 0.5, that means we are equally unsure about whether we’ll get heads or tails. For problems like coin tosses, both frequentist and Bayesian approaches seem reasonable, but when you’re quantifying your belief that your favorite candidate will win the next election, the Bayesian interpretation makes much more sense. (Kurt xix)

Kurt does a pretty good job at introducing Bayesian statistics, and how the general thought process of Bayesian stats in pretty in tune with normal logical reasoning. I really like the example of an election, there are no real previous elections to help predict the outcome here (unless this is a second term something) but for examples sake, we’d be predicting the outcome of an election based on all the prior data collected during campaigns. Things like policies, primaries, T.V. appearances, pop culture knowledge, etc. would all influence the conditional probability of an election type event. This example, for me, clearly separates what is a Bayesian thought process from a frequentist problem. In election type events there may not always be a frequency distribution or repeated events to pull a probability from.

This comparison ends it here and covers the one crucial detail of the first chapter without going into some of the basic math exercises Kurt does to put probabilities into equations.

Chapter 2+ Bayesian Statistics the Fun Way, by Will Kurt

Probability and ‘negation’

There must be an explanation for this choice of explanation -

Another important part of logic is negation. When we say “not true” we mean false. Likewise, saying “not false” means true. We want probability to work the same way, so we make sure that the probability of X and the negation of the probability of X sum to 1 (in other words, values are either X, or not X). We can express this using the following equation: P(X)+¬P(X) = 1 (Kurt 14)

- ¬ in this equation means the negation

Kurt continues on about the fundamentals of this math P(X)+¬P(X) = 1 when really it seems easier to just say that the probability of something happening and the probability of something not happening must add to 1. Either my favorite actress wins the best actress Oscar or she doesn’t. The sample is either predicted class A or class B… but perhaps the concept of negation carries over past this textbook.

Odds and probability

Calculating the probability of your belief in something can be calculated if you’re willing to make a bet on it…

Lets say you are very confident in your ability to absolutely brick your best friend in a game of Super Smash Bros., so confident in fact, you put down a fair wager… “If I win, you only owe me $10, but if you win I’ll happily send you a personalized venmo for $500”

With this bet, you have already assigned a probability your belief in your ability to beat your friend in a game of Smash. Lets work through it.

500 to 10, this is the bet you made to your friend, and is actually the equation for odds. m to n or m/n.

Your odds represent how many times more strongly you believe there isn’t an article than you believe there is an article. (Kurt 14)

In our case, you believe:

P(HI will win the Smash match) = 500, P(HMy friend will win the Smash match) = 10 = 500/10 = 50

You believe you are fifty time more likely to win than lose. And now we can assign a probability to this…

If you believe the P(HI will win the Smash match) is 50x more likely than P(HMy friend will win the Smash match) (lets switch to A and B to save space), then you believe P(Ha) = 50 * P(Hb). And since we know from above that the probability of something happening and the probability of something not happening must add to 1, P(Ha)+¬P(Ha) = 1. And here the ¬P(Ha) is just P(Hb), now we can get to the good stuff, algebra.

So, P(Ha) = 50 * P(Hb), and P(Ha)+¬P(Ha) = 1, therefore…

P(Ha) = 50 * (1 - P(Ha)) =

P(Ha) = 50 - 50 * P(Ha))… now add 50 * P(Ha)) to both sides…

51 * P(Ha) = 50… and divide both sides by 51

P(Ha) = 50/51

50/51 = .98 = P(Ha)

Now all this math quantifies your belief that you will 3 stock your best friend on final destination. You might be overconfident.

Now what did all this teach us?

That we can generalize the equation for converting odds to probability to…

P(H) = O(H) / 1+O(H)

Where O = Odds. You can try it for yourself. The 1 comes from adding P(H) to both sides where we end up adding P(H) to P(H).

This summarizes Kurt’s introduction to odds to odds and is very well done.

Probability and the product rule

I won’t spend long here because it seems simple enough. The probability of A and B occurring is simply P(A) * P(B). The product of A and B.

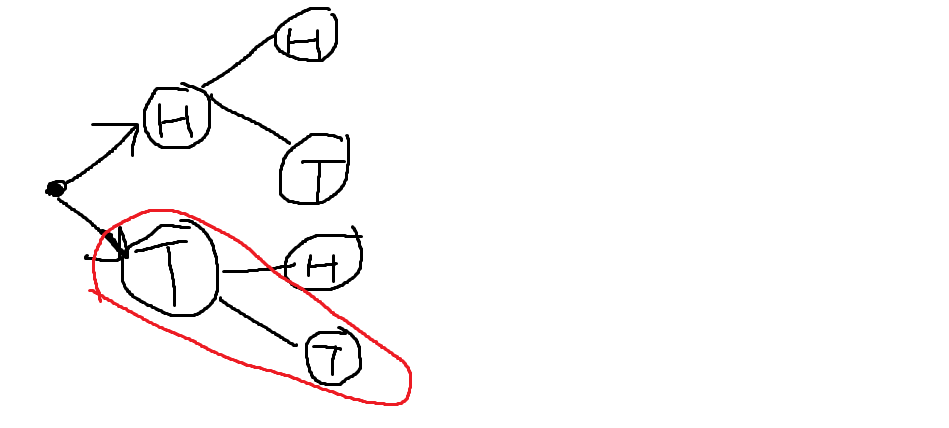

Here is a simple graph representation of why P(A,B) = P(A) * P(B), and also my submission to the Louvre.

Probability of flipping two tails when flipping two quarters:

Here we can clearly see that there is only one path out of four that results in two tails.

Here we can clearly see that there is only one path out of four that results in two tails.

1/4 = .25

We also know that the P(Flipping Tails) = .5 in a perfect world. So if flipping tails is event A

and flipping tails is also event B we get…

P(A, B) = P(Flipping Tails, Flipping Tails) =

P(Flipping Tails, Flipping Tails) = P(Flipping Tails) * P(Flipping Tails) =

P(Flipping Tails, Flipping Tails) = .5 * .5 = .25 = 1/4. Perfect.

P(A,B) = P(A)*P(B)

Probability and the Sum Rule

For mutually exclusive events, meaning if one occurs the other cannot. Then the probability of A or (not and) B occurring is P(A)+P(B).

An example of mutually exclusive events is rolling a 1 or a 2 on a six sided die in 1 roll. You can either roll a 1 or a 2 on one die, in one roll, not both.

Combining probabilities for mutually exclusive events is very easy and intuitive. Now finding the combined probability of non-mutually-exclusive events requires a little more brain activation.

…we know that P(heads) = 1/2 and P(six) = 1/6, it might initially seem plausible that the probability of either of these events is simply 4/6. It becomes obvious that this doesn’t work, however, when we consider the possibility of either flipping a heads or rolling a number less than 6. Because P(less than six) = 5/6, adding these probabilities together gives us 8/6, which is greater than 1! (Kurt 28)

When adding together probabilities for non-mutually-exclusive events, we incorrectly double count the events in which both things happen. So in order to account for this, we must remove it. Good thing we know that the probability of two events occurring is P(A,B) = P(A)*P(B). If we apply this to our sum rule for mutually exclusive events, we arrive at the equation for the sum rule for non-mutually-exclusive events.

P(A or B) = P(A) + P(B) - P(A,B)

Bayesian Statistics, The Fun Way, by Will Kurt

1: http://jakevdp.github.io/blog/2014/03/11/frequentism-and-bayesianism-a-practical-intro/